Tutoring News Post

Are there flawed questions on the SAT, ACT, GRE, GMAT, and LSAT exams? Yes, of course there are.

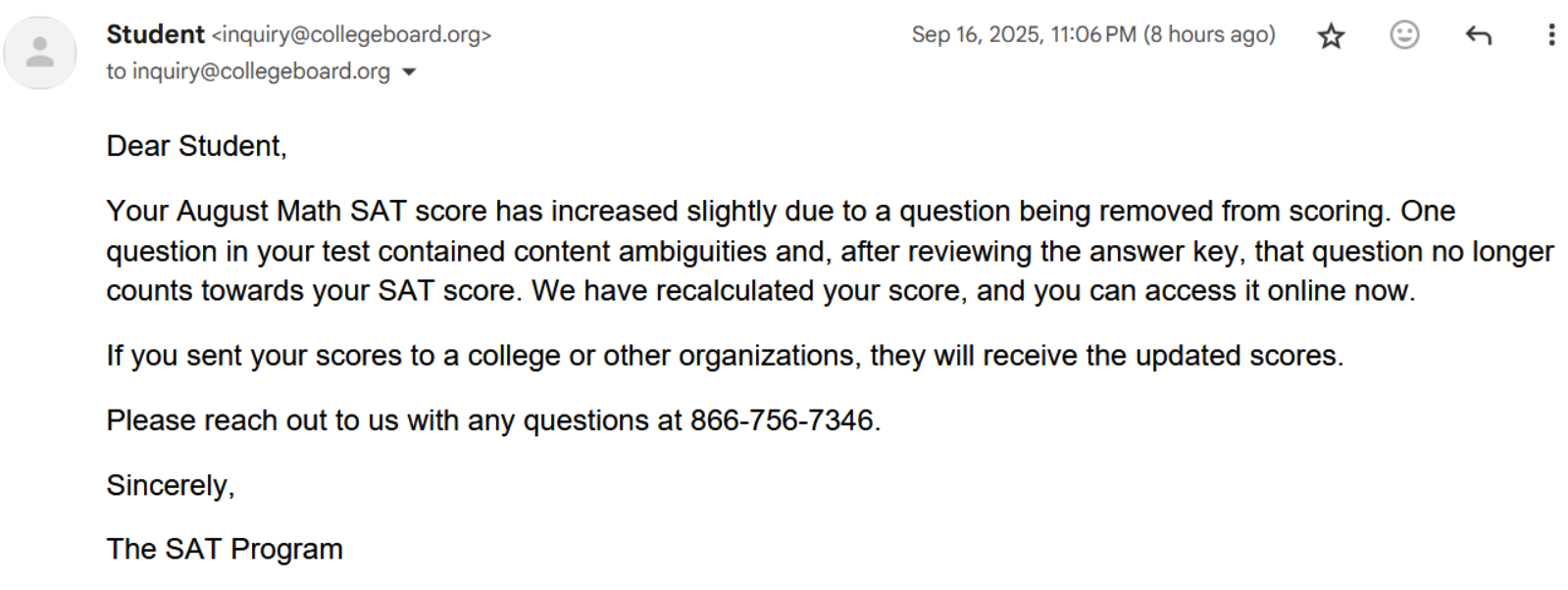

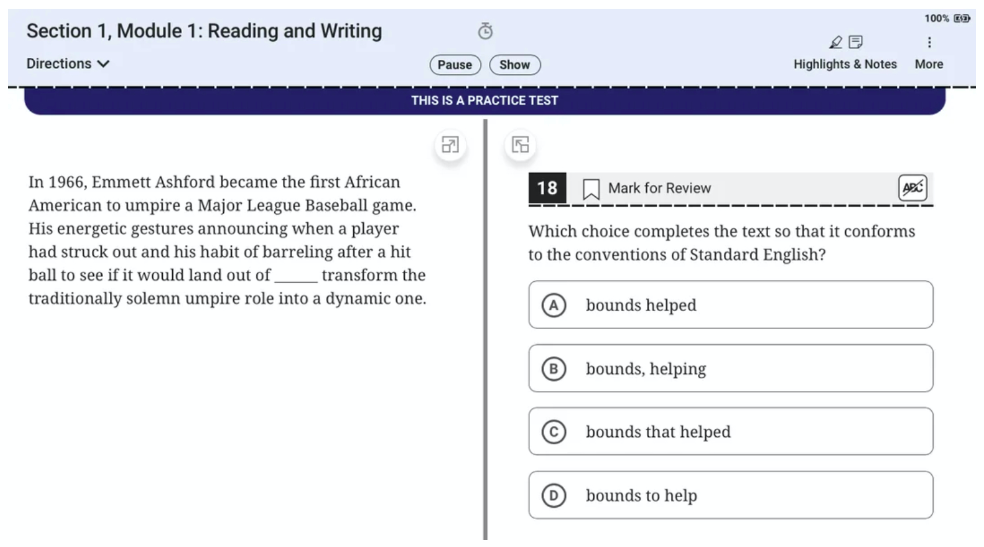

May 20, 2025: Attempting to improve your test scores on a complex, highly competitive standardized exam such as the SAT or LSAT is not for the faint of heart. For most, it is a struggle that requires hard work, perseverance, dedication, and determination. According to the data, only 2% of students will achieve score gains of 2 standardized deviations or more, meaning that such large improvements (20 points on the LSAT, 400 points on the SAT, 10 points on the ACT, 18 points on the GRE, 180 points on the GMAT Focus) are simply not achievable for the vast majority of test-takers, other than the very lowest of scorers. Meanwhile, 82% of test-takers won't improve more than 1 standard deviation. In many cases, even students who achieve nearly perfect grades at top colleges and universities can struggle to crack the top 50, 25, or 10 percent of scores. They might start to wonder: “Am I not smart enough for this next level of increased competition? The test just doesn't make sense to me.” There is a reason why so many of these self-studiers fail: most standardized exams are not solely meant to test skills that are already well-understood by educated graduates. The tests require not only fundamental critical reading, writing, logic, and math knowledge, but also a highly esoteric and specialized curriculum rarely taught at the high school or college level--vocabulary terms, rules, equations, concepts, and techniques that can be nearly mastered over time, but only with patience and the right instruction / resources. Why do I say "nearly" mastered? Well, consistent perfection is impossible on tests that are themselves imperfect. These are difficult, highly technical, subjective, and wordy exams created by fellow human beings like us: people who report to bosses and punch clocks for big corporations based in boring office parks in places like New Jersey, Iowa, Virginia, and Pennsylvania. As humans, they are not infallible, and they even sometimes write questions that are so obviously flawed that they must be removed from scoring after the exams have been administered (or even scored!) -- despite the embarrassment this surely causes on Monday mornings at the company headquarters. Of course, their response is quite literally correct, because these students infer that the question is asking for an additional conclusion--thus concluding that a summary of what has already been said is not enough. Yet in many cases, the correct answer to a "most strongly supported" question is an answer that has either already been stated, or MUST be true, even though that is technically not correct according to the precise wording of the question. Let me provide another example. Nearly all Reading Comprehension questions that ask what the author would “most likely agree” with are actually asking what the author has literally already stated in the passage, not what they “might” say--even though the question is clearly worded as a hypothetical. As a long-time tutor, I can certainly relate: I am often tasked with the unenviable job of having to justify an answer with which I don’t completely agree. Information about the quirks of these exams falls into the category of what we call "testwise knowledge." Testwise knowledge is information that is not known to the general public, and that instead pertains to the patterns and tendencies of the question writers themselves: human beings with flaws, idiosyncrasies, and assumptions that, despite their best efforts to make their questions unassailable, can cause them to write objectively flawed questions. For example, I once had an AP US History teacher who loved to put "D: all of the above" as the correct answer on his semester exams: it was correct far more than 25% of the time. Thus, if I wasn't sure on a particular question, then I would always guess "D." I often answered these questions correctly--not because I remembered the required historical facts, but because I remembered the tendencies of the test maker and took an educated guess based on prior experience. So, what gives? Why is the internet full of self-proclaimed LSAT experts and LSAC apologists who claim the exact opposite: that every LSAT question is perfect, and that there is one absolutely correct, defensible answer, and four absolutely wrong, indefensible answers? That every question is 100% logical, if you approach the questions the right way (their way, of course)? First, this type of response is a small-intellect phenomenon largely driven by insecurity. It's almost as if these commenters (often fledgling LSAT tutors trying to drum up business) believe that admitting that some questions are poorly written or vague is akin to not understanding the LSAT well enough. These individuals quite often simply reverse-engineer their explanations from LSAC's official answers, thus perpetuating a type of confirmation bias. After all, many LSAT questions literally ask for the "best" answer, or the answer that "most" weakens / supports, etc... so it is absurd to claim that the correct answer is "completely" correct, or the wrong answers are always "completely" wrong. In fact, the distinction between the "best" answer and the second-best answer is often razor-thin--and based upon somewhat arbitrary (but learnable and predictable) preferences on behalf of the test maker. Second, LSAC has been known to actively cajole well-known LSAT tutors into signing an NDA (non-disclosure agreement) in order to become an "LSAC licensee." This status offers minor benefits, such as being able to login to student LawHub accounts to monitor their progress, but comes with a big cost: you are not allowed to criticize LSAC or LSAT questions in any way, shape or form! Thus, there are presumably many other private tutors out there who would like to join me in publicly criticizing the occasional LSAT question--and who presumably feel free to do so when discussing questions privately--but are handcuffed by the NDA they felt pressured to sign under the vague threat of legal action. While it is of course true that the vast majority of official LSAT Logical Reasoning (LR) and Reading Comprehension (RC) questions are rock-solid if you analyze them correctly, others are certainly suspect, and full of flaws. And because LSAC wasn't able to convince me to sign its NDA, I am still legally allowed to speak my mind on the issue—which is a relief, because I wouldn’t be able to teach the exam as effectively otherwise. In the test-prep community, it's been an open secret for decades that LSAC’s quality control for new LSAT questions is sometimes lacking. That's why, at least in the old days of the paper LSAT, many questions would be removed from the exam before final scoring / being disclosed, like in the SAT example provided above. And yes, LSAT question removal on official exams is relatively rare, but this doesn't change the fact that truly flawed questions can still occasionally make it all the way to official LSATs. With nearly 100 disclosed PrepTests, that's a lot of flawed questions total. And those are just the questions that LSAC decided were so bad that they had no choice to remove, meaning that other flawed questions could have still remained, especially on non-disclosed PrepTests. LSAC is judge, jury, and executioner in these matters, and there has never been any third-party review process to objectively evaluate LSAT question validity. At the end of the day, the LSAT is a flawed test, written by intelligent but flawed humans who work for a flawed corporation. Luckily, the LSAT (like all standardized tests) can still be 99% mastered, of course--by sometimes translating what the test means from what it actually says, and by aligning your own personal question analysis and interpretation with the "testwise" quirks, rules, and patterns of the exam. To instead insist that every exam question is perfectly worded and beyond reproach not only reeks of a lazy intellect, but is also counterproductive to student improvement. -Brian Dear College Board: "Out of bounds," really? It's called a "foul ball." Isn't that common knowledge in the US? Baseball is our national pastime, after all. In addition, the above question incorrectly uses the word "if" (appropriate when only one scenario is considered: "if it rains, then the game is cancelled") in place of the word "whether" (appropriate when more than one scenario is considered: "I don't know whether it will rain"). In this instance, there are two possibilities at play: the batted ball may or may not be foul. Thus, the actual correct answer should be "...to see whether it would land in foul territory helped transform..." There clearly aren't many sports fans at the CB corporate headquarters, but I would expect more from its grammarians. This is a real digital SAT question, from Bluebook Test 10, Reading and Writing Module 2 Hard (the official answer is Choice A). It can also be found on page 329 of the Official Digital SAT Study Guide.

|